By Les Johnson, Birmingham City University

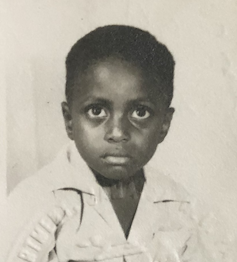

As a young boy in 1962, I remember arriving in England from Jamaica on a BOAC jet plane. It seemed to me like I was going to the moon – the air hostess who accompanied me was one of the first white people I had ever seen. My father greeted me eagerly at London’s Paddington station, amid the swirling smoke of steam trains. It had been two years since we last met, but I recognised him immediately.

Fourteen years earlier, the arrival of the Empire Windrush at London’s Tilbury docks in 1948 was a pivotal moment in British history, marking the beginning of a significant wave of migration from the Caribbean. This became known as the Windrush generation, and signified a new chapter in the history of the United Kingdom. Since then it has assumed a symbolic status, commemorated annually on Windrush Day, observed on 22 June.

This article is part of our Windrush 75 series, which marks the 75th anniversary of the HMT Empire Windrush arriving in Britain. The stories in this series explore the history and impact of the hundreds of passengers who disembarked to help rebuild after the second world war.

This turning point reformed Anglo-Caribbean identities as the Windrush generation settled in Britain, leaving their mark on history, society and culture. The arrivals serve as a poignant reminder of the dynamic and fluid nature of migration, identity and societal transformation. But how did this momentous event come about, and what were the factors that led to the settlement of these British citizens?

These questions are important because Windrush history is not included in the UK school curriculum, resulting in an incomplete view of Britain’s history of cultural diversity. Race equality think tank, the Runnymede Trust, has described the Windrush story as “an integral part of British history”.

While there are now numerous celebratory events and commemorations on or around Windrush Day, once the festivities end, there is little permanence. There are no major collections or permanent Windrush exhibitions. There has been no museum dedicated to its history with the significance of other major British museums. And there is no major institution for children to view the legacies of the Windrush generation and their impact on Britain. These are just some of the reasons I recently founded the National Windrush Museum.

Coming to Britain

The British invitation to Caribbeans to come to Britain after the second world war can be traced back to the British Nationality Act of 1948. This conferred British citizenship and the right to settle in the UK on all people from the British colonies to help rebuild the country.

The Windrush generation refers to the people who migrated from Caribbean countries to the United Kingdom between 1948 and 1971. However, Caribbean immigration did not cease after this period, and migrants have settled ever since, influencing Britain’s demographic composition.

Major urban centres like London, Birmingham, Manchester, Bristol, Liverpool, Leeds and Preston became focal points for these communities, where they established vibrant neighbourhoods and thriving cultural institutions, contributing to the overall diversity and multicultural fabric of these cities.

Despite the open invitation, the reception the Windrush pioneers received was often hostile. Caribbean migrants were (and still are) subjected to poor housing conditions, with accommodation in hostels often overcrowded and lacking basic amenities. In 1948, an underground shelter in Clapham South tube station was used as temporary housing for people from the Caribbean.

The types of employment available to the Windrush generation were often limited to low-paying jobs such as cleaning, factory work and driving. Created the same year in 1948, the National Health Service (NHS) has been an important source of employment for members of the Windrush community since its inception.

Many Caribbean migrants found work in hospitals, nursing homes and other healthcare facilities, playing a crucial role in the development and functioning of the NHS. They contributed their skills, dedication and expertise, helping to shape and improve healthcare provision in the UK.

Some devised ingenious self-help micro-financing schemes such as the “partners” initiative, where small groups banded together and shared from the combined pot of money weekly. This is how many of the Windrush generation afforded air fares to send for their families – and how my parents were able to send for me.

The institutional racism and poor conditions endured by the Windrush generation led to people starting their own businesses: barbers and hairdressers, fashion and design, restaurants and cook shops, a variety of trades, market stalls, independent black churches and dancehall music. These businesses were important not just in generating a living, but also in developing flourishing communities and creating black British culture.

In addition to their contribution to the workforce, the Windrush generation and their descendants have made a significant social and cultural impact on British society. They brought with them their Caribbean culture, art, sports, traditions, and customs, enriching the cultural landscape of the United Kingdom. From food and music to fashion, literature, language, and even cricket, Caribbean influences became ingrained in British popular culture, fostering a sense of diversity and multiculturalism.

The Windrush pioneers

Sam King MBE was one of the notable figures of the Windrush generation who played a significant role in the establishment of the annual Windrush Day on 22 June. Born in Jamaica in 1926, he served in the British Army during the second world war before coming to Britain in 1948. King went on to become the first black mayor of Southwark in London, and was involved in a number of community projects and organisations.

Other important Windrush figures include Claudia Jones, a political and pioneering journalist; Stuart Hall, a cultural theorist and political activist; Bill Morris, a trade union leader who became the first black general secretary of the Transport and General Workers’ Union; Diane Abbott, who became the first black woman to be elected to the British parliament; and Bernie Grant, who also served as a MP and was a prominent campaigner for racial equality and social justice.

Hall was a Jamaican-born British cultural theorist who played a significant role in shaping our understanding of race, identity and culture. Hall argued that identity is not fixed, but rather is constructed through social and cultural practices. He also emphasised the role of power and control in shaping culture.

In the context of the Windrush generation, Hall’s theories are particularly relevant, as they help us to understand the ways in which Caribbean migrants and in particular the Windrush generation identities were constructed and represented in British culture.

The Windrush scandal

One of the most shameful episodes in this history is the Windrush scandal, which saw people who had lived in the UK for decades – including some who had friends who arrived on the Windrush – being wrongly deported or denied access to public services like the NHS.

This British government scandal came to light in 2017, when British citizens of Caribbean descent who had migrated to the UK between 1948 and 1971 were wrongly classified as illegal immigrants. They then faced deportation, detention and some even lost their homes and livelihoods. This gross injustice has affected many lives, highlighting the systemic racism that exists in Britain. Its impact is still being felt today.

The Black Lives Matter movement has been instrumental in bringing attention to these issues, and its importance in highlighting the systemic racism in Britain cannot be overstated. The toppling of statues of figures linked to the slave trade and colonialism, such as Edward Colston in Bristol and Robert Milligan in London, sparked a wider conversation about decolonisation at all levels of society and the need to confront Britain’s colonial past.

The National Windrush Museum

According to the Museums Association there are about 2,500 museums in Britain. Yet there is no black culture museum or established school curriculum that focuses on the heritage of the Windrush generation. In 2021 I founded the National Windrush Museum which I chair. The museum plays an important role in collecting, researching, documenting and exhibiting artefacts and stories about the Windrush generation and those who came before and after them.

The museum provides a vital link to the past and a gateway to the future, enabling us to understand and appreciate the contributions of the Windrush generation to Britain. It will also serve as a valuable resource for schools and universities, providing an opportunity for collaboration in the development of curricula, research and study centres and libraries around the world.

Many stories and hidden narratives of the Windrush generation need to be unearthed, told and preserved. As part of the second wave of Windrush settlers and as an academic researcher who innovated the concept of cultural visualisation, this is important work. Cultural visualisation involves the visual research, portrayal and analysis of various aspects of culture, including music, film, fashion, visual arts, dance, literature and more.

My work looks at “doing culture differently” and I wanted this new venture to adopt the idea of “doing museums differently”. The National Windrush Museum provides a life laboratory in which to explore and develop this concept, which I hope will have a significant cultural impact on the heritage sector.

The 75th anniversary of the Windrush generation is a poignant opportunity to shed light on a momentous event in British history so often neglected in our schools. This milestone marks a transformative chapter that reshaped Britain’s fabric and ushered in a vibrant new culture.

The founding of the National Windrush Museum stands as a vital, moving and significant historical moment. By documenting, exhibiting and explaining the enduring legacies of the Windrush generation, the museum becomes a powerful testament to their contributions. Its ethos fills a crucial gap in our understanding of Britain’s history, ensuring that these stories are preserved and celebrated as integral parts of our national narrative.![]()

Les Johnson, Visiting Research Fellow, Birmingham School of Media, Birmingham City University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.